Buddhist practice and Buddhist art have been inseparable in the Himalayas ever since Buddhism arrived to the region in the eighth century. But for the casual observer it can be difficult to make sense of the complex iconography. Not to worry—Himalayan art scholar Jeff Watt is here to help. In this “Himalayan Buddhist Art 101” series, Jeff is making sense of this rich artistic tradition by presenting weekly images from the Himalayan Art Resources archives and explaining their roles in the Buddhist tradition.

Himalayan Buddhist Art 101: Why Paintings Are Made, Part 2

Art has been traded as a commodity in Tibet for the last several hundred years, with paintings produced in advance for sale to pilgrims and traders traveling from India, Nepal, China, and Mongolia. The marketplaces of Lhasa and Shigatse in central Tibet were the primary sources for such paintings.

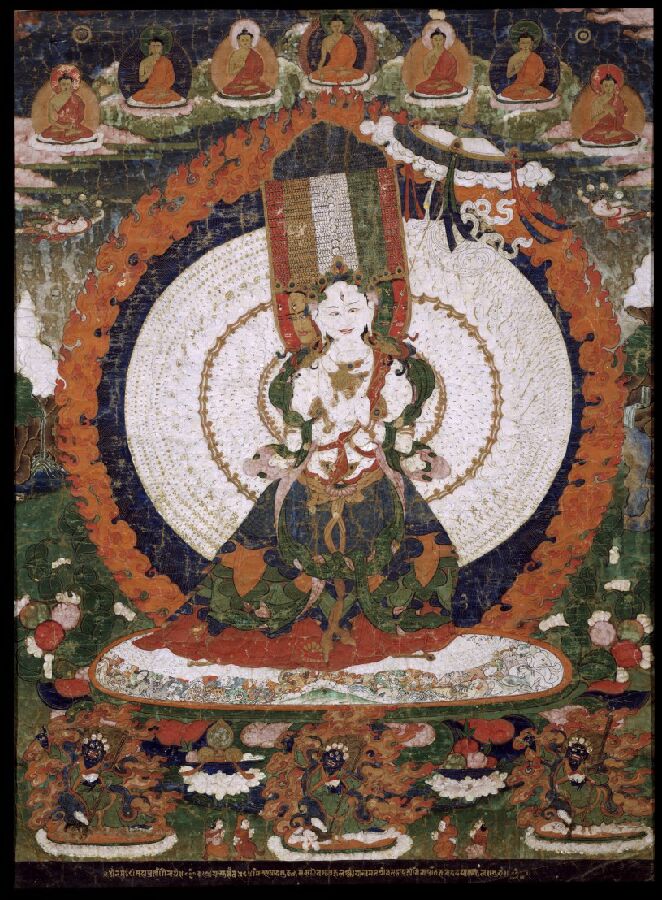

Fortunately for casual observer and expert alike, many of these paintings are very easy to identify. Visitors from Nepal were the largest single consumer market for Tibetan art. Art produced for the Nepalese travelers and traders can be identified by a black border at the bottom of the composition. Inside the black border there is often either a short or lengthy inscription in a Nepalese Newari script. The inscription almost always includes a date and the name of the donor, along with the special purpose of dedication and the name of the individual to whom the merit is dedicated.

The first example depicts Amitabha Buddha in the Pure Land of Sukhāvatī, the famed Western Paradise. In the rainbow circle he is accompanied by the Eight Great Bodhisattvas of Mahayana Buddhism. At the bottom of the composition you’ll find a lengthy inscription—three lines deep—in a Nepalese script.

The second example is of the female meditational deity Sitātapatrā, White Parasol Goddess. At the top are the Seven Buddhas of the Age, and below, the Three Mahakala Brothers acting as special protectors for the practices of Sitātapatrā. On the black border at the bottom of the composition is a short, single-line inscription stating that the painting was dedicated by a loving husband to honor the memory of his deceased wife in 1864.

It remains unclear whether artists in Tibet wrote these inscriptions or whether they left them blank, only to be applied by the travelers upon their return to Nepal. The process of inscription and the identity of the scribes remain mysteries in the history of the commodity and pilgrimage souvenir trade between Tibet and Nepal.

View other pilgrimage paintings at Himalayan Art Resources, here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.